Particle sizes

and impact on filtration of fabric masks

This post aims to provide basic understanding of mask filtration through a broad overview of particle physics, disease transmission, and biology of particles.

Introduction: How well do fabric masks filter?

The question of how well any specific mask fabric combination blocks SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, turns out to be rather complex. In general, fabrics filter large particles well and small particles poorly, where the transition from "well" to "poor" coincides with a range of particle sizes that may or may not be key to SARS-CoV-2 transmission. For example, N95 respirators are tested with roughly 0.3μm particles, chosen because they are the most difficult to filter and because particles of any size may be present in industrial environments. However, larger and easier to filter particles likely dominate SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Thus, a mask with relatively poor filtration of 0.3μm particles may still provide good protection against SARS-CoV-2. Presently the scientific community lacks consensus regarding which particle sizes are most involved in transmission.

To interpret a filtration measurement we must pull together knowledge from multiple fields of study. Particle physics describes how a particle moves through air and how it interacts with a mask or filter, including particle size effects. Biology characterizes when we produce virus-laden droplets, what sizes, and how much virus may get us sick. Disease transmission studies look at when and how the disease is transmitted in different environments and situations. The three combined enable holistic insights not available from any single discipline.

Although many papers have been published in these three fields, especially since the onset of the pandemic, science still lacks consensus on what size particles dominate COVID-19 transmission and against what particle size we should test our masks. This article aims to present some of that data and build a cohesive understanding from what we know, even if we don't know everything.

Physics of particles

Size matters, both for particle transit between infected and healthy persons, and for particle capture by masks or filters.

Physics of particles in air

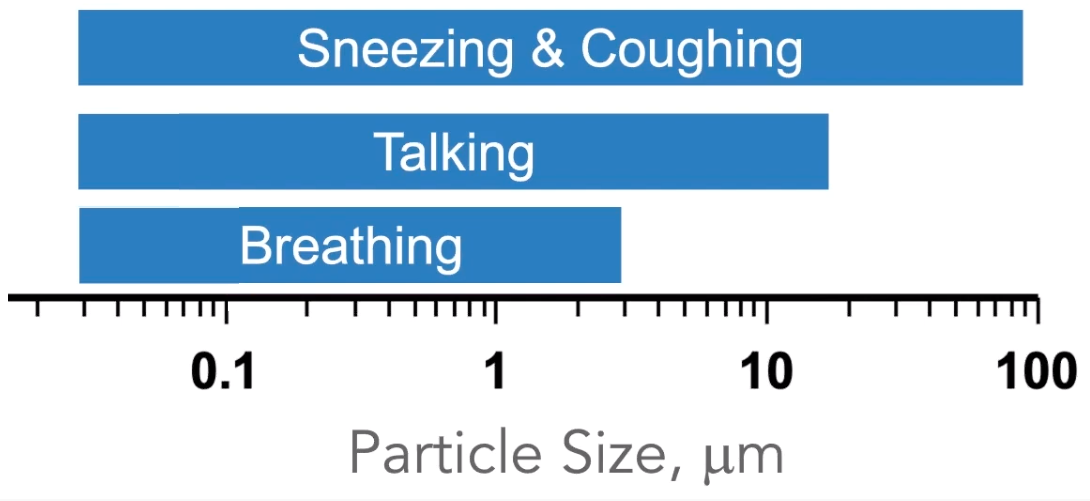

When we cough, speak, and even breathe, we produce droplets which can carry various germs from our mouths and respiratory systems into the environments around us. Small particles carry small viral loads, can float in the air for minutes or hours, and dry up within a fraction of a second. Large particles can carry large viral loads and fall to the ground quickly. This section provides insights into the paths of different sized particles.

Ballistic droplets.

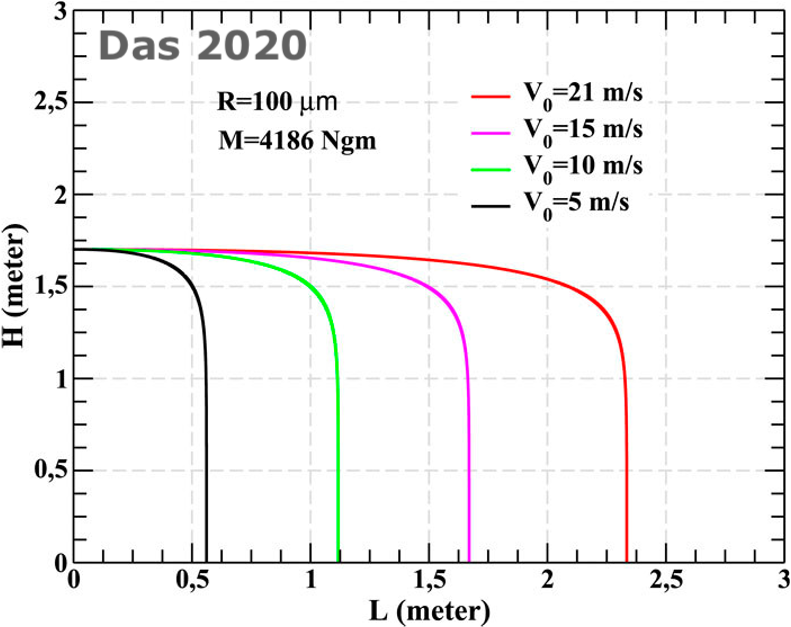

How far particles travel depends on their size and ejection velocity. Small particles with very long falling times tend to travel with air currents and how far they travel is mostly a matter of ambient air flow. Large particles with short falling times travel ballistically, like a cannonball, and how far they fly before landing on the floor very much depends on initial velocity. For example, [Das 2020] calculates distance traveled by a 200μm diameter (100μm radius) droplet for different ejection velocities, up to 21 m/s which is close to the fastest for droplets originating from a cough.

Social Distancing - The 6ft Rule. Particle behavior in air informs understanding of guidelines around COVID-19 transmission. The 6ft rule is largely based on protecting against large ballistic droplets. As we see in the figure from [Das 2020], 200μm diameter particles coughed out at 18 m/s travel 6ft, so 6ft distancing should protect well against large droplets from most coughs and sneezes. With regards to smaller droplets, the 6ft rule is a proxy for time [Salter 2020] and airborne particles (<50μm) will behave as smoke [Jimenez 2020] with a higher concentration close to the emitter. For example this video by Ryan Davis on Twitter shows how 50μm particles dance in the still air of a lab. The 6ft rule keeps others out of the most dense part of the particle cloud, but just like cigarette smoke airborne particles can build up in a poorly ventilated room or waft further than 6ft. Masks are an important disease mitigation method since they stop the ballistic droplets and greatly reduce the concentration of airborne droplets when worn by an infected person.

The table below quantifies how long particles of various sizes remain airborne in still air.

| Droplet falling time as a function of size (in Morawska 2006, in turn compiled from Wells, 1934 who assumed zero initial velocity and calculated the time from Stokes' and Newton's laws.) | |

| Droplet diameter (μm) | Falling time of 1 m (s) |

| 1000 | 0.3 |

| 100 | 3 |

| 10 | 300 |

| 1 | 30,000 |

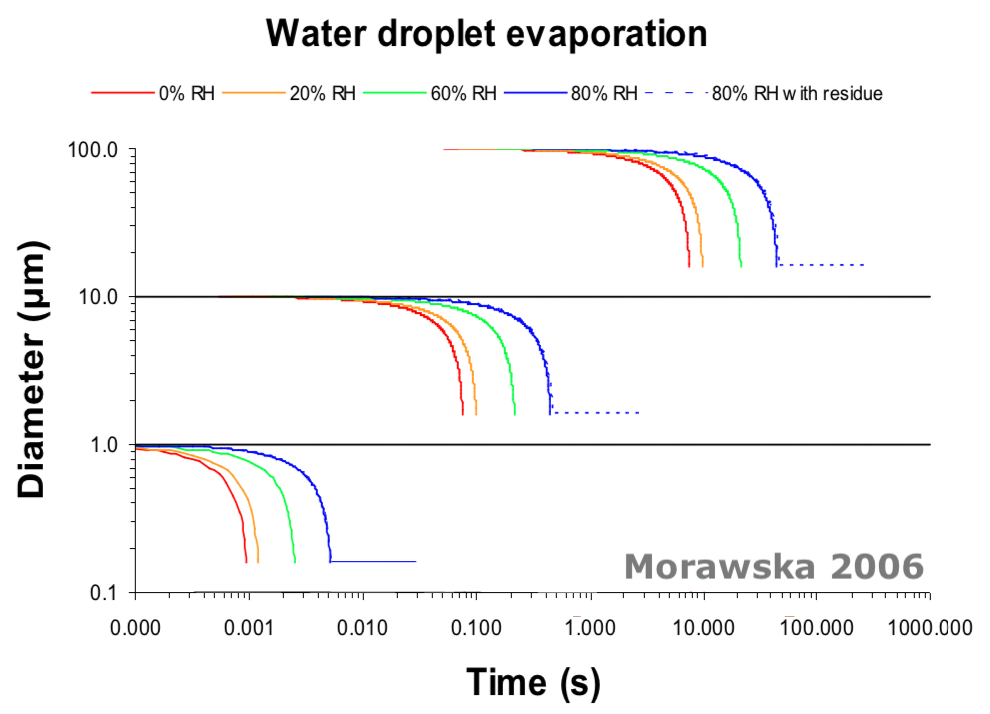

Evaporation: The moment droplets leave our mouths and noses, they start to dry. For example, a 1μm droplet dries up within a couple milliseconds, a 10μm droplet within 1/5 of a second, and a 100μm droplet is likely to fall to the floor before it dries fully

[Morawska 2006].

Further reading: If you found this section interesting and would like to learn more, [Jimenez 2020] and section 2 of [Salter 2020] provide easily readable discussions.

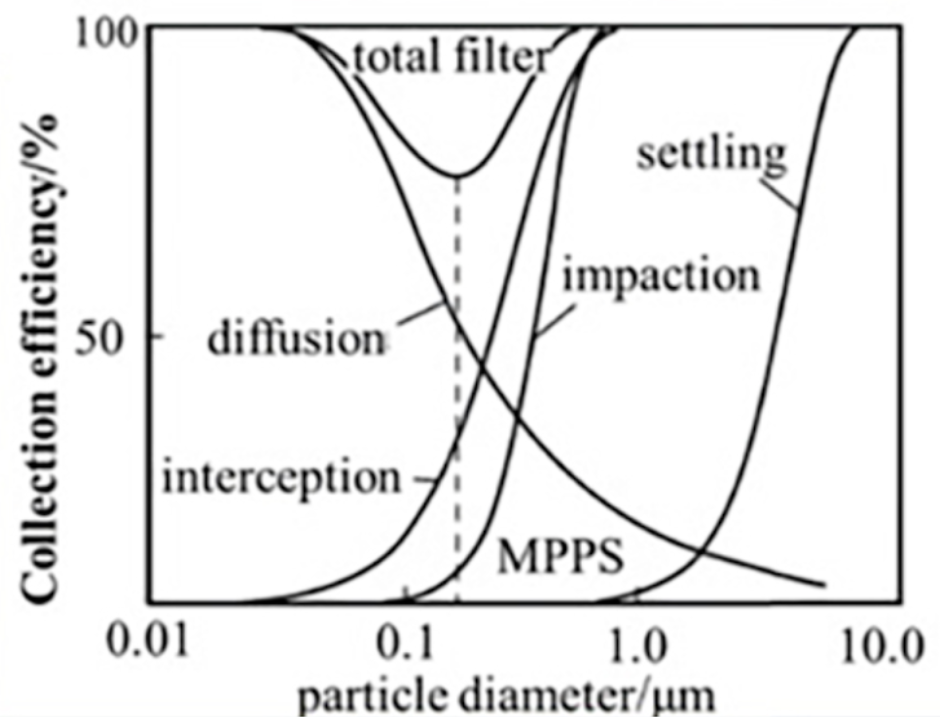

Physics of particle capture

Particles can be captured by a mask through one of several physical mechanisms, including: straining, inertial impaction, interception, diffusion, and electrostatic attraction. Straining, inertial impaction, and interception are the dominant collection mechanisms for large particles ( > 0.3μm in diameter), while diffusion dominates for the smallest particles (<0.3μm ). (Figure from Hinds, Aerosol Technology, Wiley Interscience, 2001.) The Most Penetrating Particle Size (MPPS) occurs where all of the capture mechanisms are weak, around 0.3μm. |

|

| Straining happens when a particle is larger than the gaps between the fabric fibers, and the particle gets trapped in the gap. |

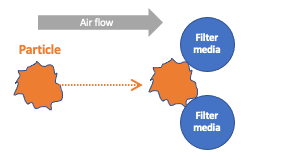

| Inertial Impaction happens when a particle has large enough momentum to collide with a filter fiber, rather than following the gas stream around the fiber. |

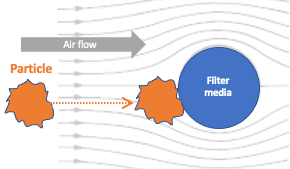

| Interception happens when a particle in the air stream touches a fiber and has too little momentum to keep going, and so remains adhered to the fiber. |

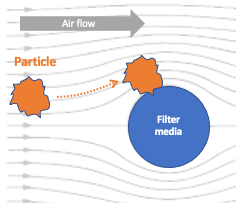

| Diffusion happens when random (Brownian) motion of a particle causes that particle to contact a fiber. Diffusion dominates for small particles and at very low air flow rates. |

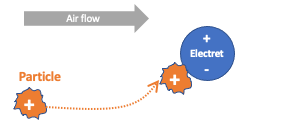

| Electrostatic attraction happens when charged particles are attracted to an oppositely-charged medium. Some masks (e.g., N95s) incorporate electrically charged fibers (electrets) to enhance filtration. It is important to note that electrets degrade with washing and from accumulated moisture associated with reuse. |

What does all that mean for fabric masks?

Very Big Particles (>100 μm). Very big particles (>100μm) will be captured by most any fabric through sieving, impaction, or interception. The largest gaps in a woven quilting cotton (e.g., Kona) are around 100μm, so >100μm particles are caught by straining, whereas 50μm particles are more likely to be captured through impaction or interception than to find one of those gaps. This is why fabric masks work so well against large particles.

Somewhat Big Particles (10μm to 100μm). This particle size range is also subject to sieving, impaction, or interception, but many fabrics have large enough gaps between fibers that some particles will never come close enough to a fiber to be captured.

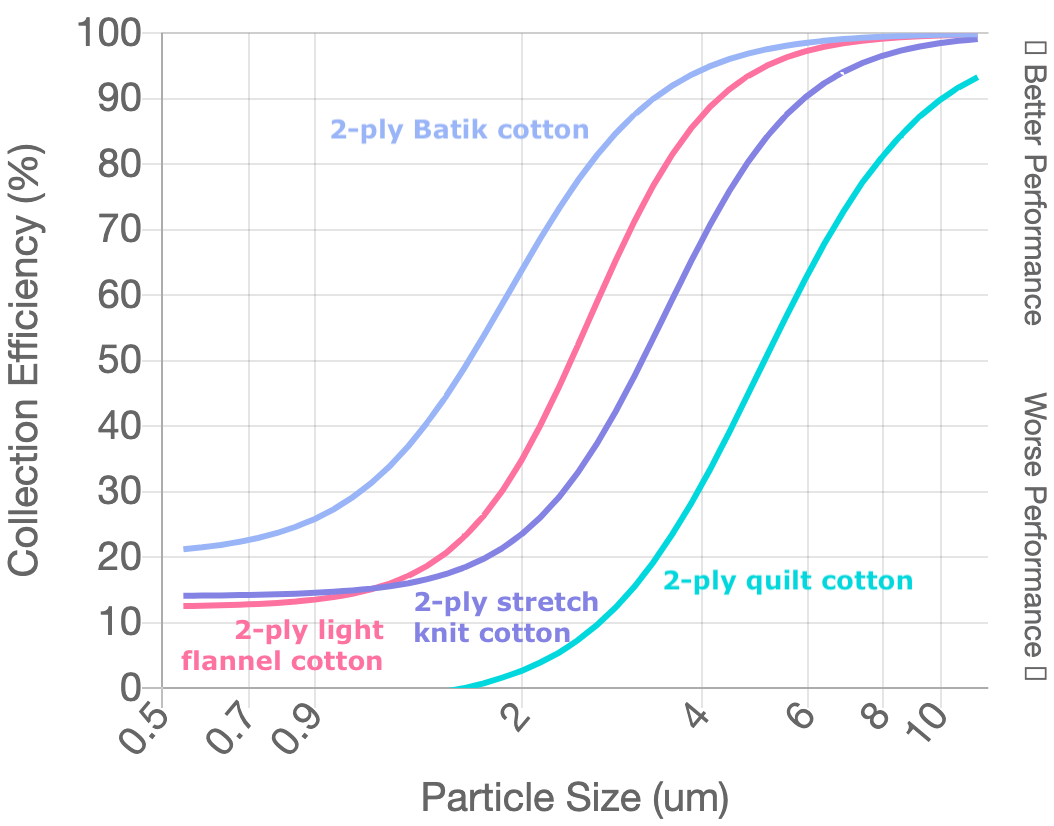

Mid-Size Particles (0.5μm to 10μm). Filtration changes substantially over this range. This plot from Colorado State University ( http://jv.colostate.edu/masktesting/ ) shows the filtration efficiency of different fabric combinations for particles ranging from 0.5 to 10μm. It illustrates trends also seen in other studies. Multi-layer cotton filters quite poorly <1μm and quite well >10μm. For example, the teal line corresponds to two layers of quilting cotton, with poor filtration of submicron particles and performance approaching an N95 for 10μm particles. However, filtration is not the only relevant metric for masks; breathability is also essential. The best filtering (light violet) line is two layers of Batik cotton. The corresponding pressure drop or breathability for Batik is 4.5 times worse than the quilting cotton, likely making a Batik mask both uncomfortable and prone to leak around the sides.

Tiny Particles (~0.3μm). Tiny particles (~0.3μm) are very hard to capture with a fabric mask, since such small particles are captured primarily through the slow process of diffusion and an inhalation pulls the particles through relatively quickly. N95s exhibit excellent filtration even for 0.3μm and smaller particles thanks to their electrets. Unfortunately electrets are not practical for reusable fabric masks since they lose their charge when washed. However, a 0.3μm particle cannot hold very many 0.1iμm viruses. So while 0.3iμm and smaller particles are a significant concern in some industrial situations, they may not be as concerning for COVID-19 transmission as we’ll discuss in the section on Biology of Particles [Sosnowski, 2021].

Disease transmission

Masks reduce COVID-19 transmission and severity, shown by population studies in people and by well-controlled data from animal experiments. This epidemiological understanding combined with physical studies of fabrics can help elucidate what particle sizes matter for disease transmission.

Studies of community masking are nicely summarized in the "Human Studies of Masking and SARS-CoV-2 Transmission" section of "Science Brief: Community Use of Cloth Masks to Control the Spread of SARS-CoV-2". In studies of small and clearly defined populations, such as 139 clients of infected hairstylists or 124 Beijing households or an outbreak on a cruise ship, masks reduced transmission by 70% to 100%. Analyses of less well bounded communities also showed that masking reduced population infection rates, though with an imprecisely bounded population it's hard to calculate a precise percentage.

Hamsters allow for better controlled studies. For example, one study [Chan 2020] inoculated hamsters with SARS-CoV-2 and then placed these sick hamsters in cages next to healthy (naive) hamsters. Some cage pairs were separated by a surgical mask barrier. Others were not. Once again, the surgical masks reduced COVID-19 transmission, but did not completely eliminate the spread of the disease. However, in the cases where there was transmission, the masks reduced the severity of the transmitted disease.

Now we can tie together epidemiology with particle physics. These epidemiological studies indicate that masks are effective at a community level, blocking enough viral particles to reduce both the number of cases and the fraction needing intensive care. As discussed in the Physics of Particles section, most fabrics filter poorly for particles 0.3μm to 1μm, increasingly better for particles 1μm to 10μm, and quite well for particles >10μm in diameter. This is consistent with >10μm particles being important to COVID-19 transmission (since medical and fabric masks reduce transmission), and with 1 to 10μm particles also playing a role (since some transmission occurs even with use of medical and community masks).

Biology of particles

Biology informs a different perspective on what particle sizes matter to COVID transmission. Some studies look at what size droplets people actually produce during different activities, others look at how much virus those droplets contain, and still others look at where particles deposit. A prevailing result is that size matters. Compared to large droplets, small droplets tend to be produced and deposited deeper in the lungs, and to carry a larger viral density.

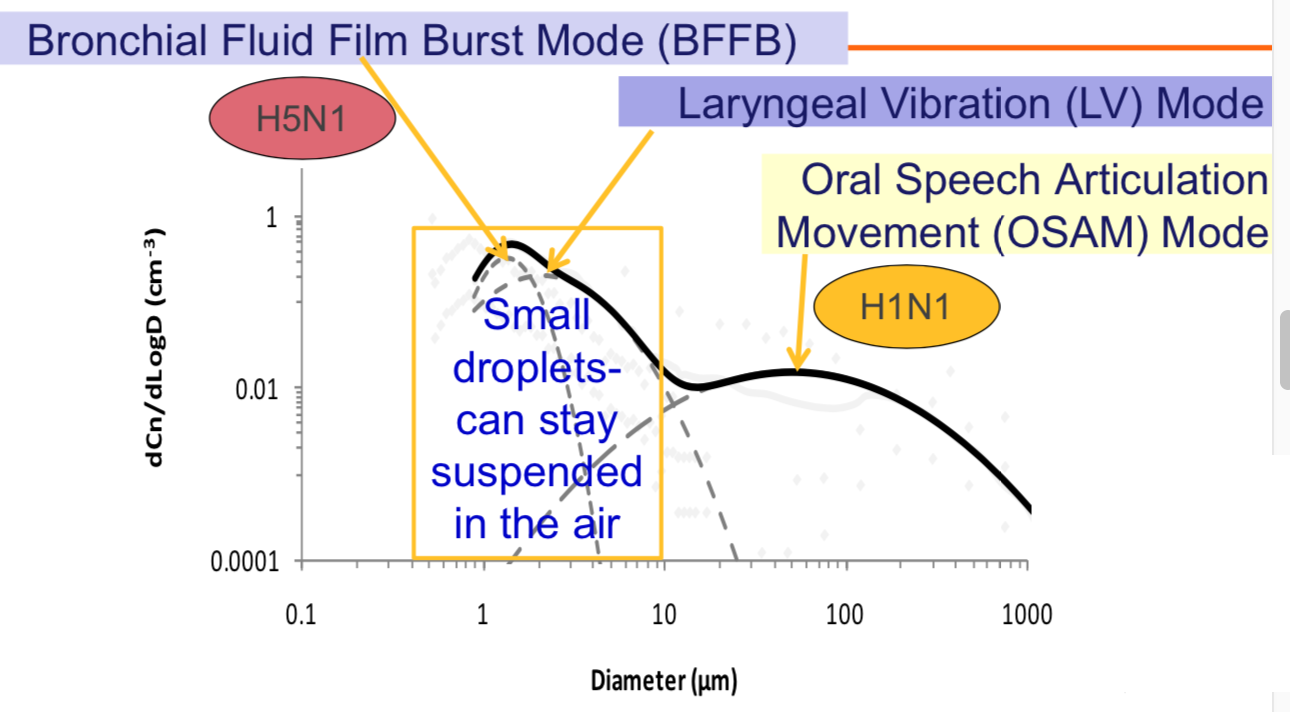

A number of studies have looked at what size droplets we produce, and the answer varies by activity and also from person to person. Broadly speaking, humans produce a wide range of droplet sizes between ~0.1μm and >100μm, and we seem to produce most around 1μm [Morawska 2009 and 2020].

Droplets produced during speech, from Morawska 2009 and 2020. Note that both axes are logarithmic. |

Volckens 2020 (4:45 in video). Note the logarithmic scale. |

Evidence from flu:

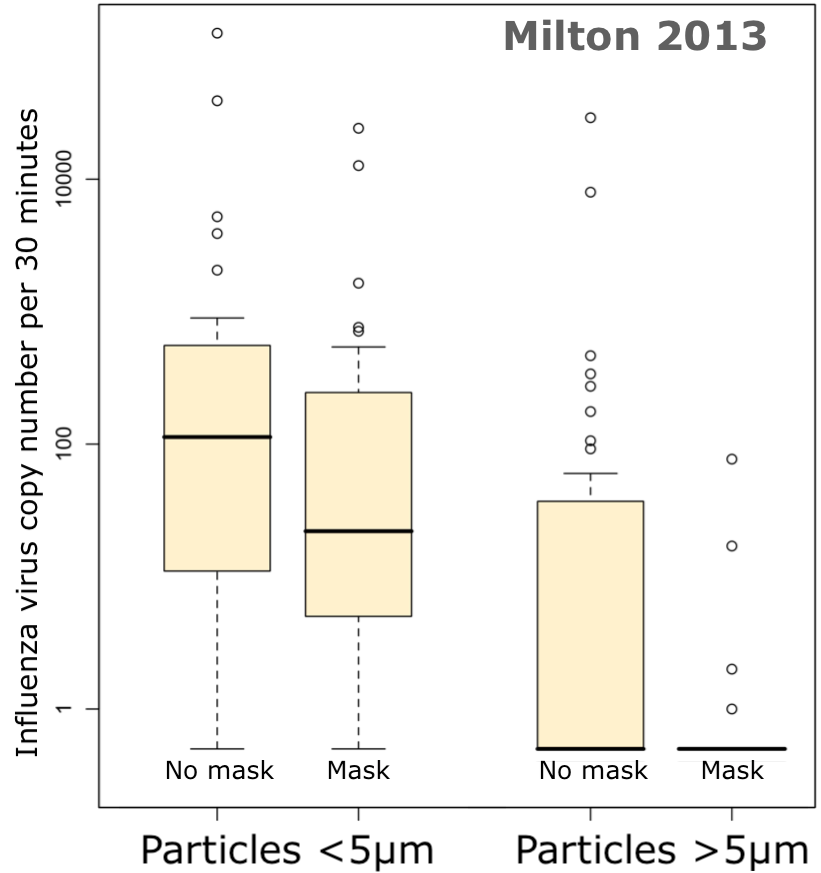

Droplets of most concern may range from 1μm to 5μm. For example,

[Milton 2013]

collected exhaled particles from flu patients and found 8.8 fold more viral copies in the ≤5μm particles than in the >5μm particles. What's more, surgical masks were much more effective at blocking the virus from >5μμm droplets (a 25-fold decrease in viral copy numbers with masking) than from ≤5μm droplets (a 2.8-fold decrease). That's a double whammy for the smaller particles: patients emit more flu virus in the <5μm particles, and those particles are less well filtered by surgical masks. Similarly,

[Lindsley 2010]

assessed droplets expelled by coughing and found that 35% of the influenza RNA was contained in particles >4μm in aerodynamic diameter, 23% was in particles 1 to 4μm and 42% in particles <1μm. Lindsley did not assess infectivity directly. In well-controlled studies in ferrets,

[Zhou 2018]

found that droplets less than 1 μm did not cause ferret-to-ferret transmission, whereas those from 1.5 to 15.3 μm did transmit infection; larger droplets were not assessed. Zhou's results also counter the idea that high particle counts necessarily imply high infectivity: while 76.8% of total airborne particles released from the ferrets had aerodynamic diameters of 0.52-1.54μm, ferrets exposed to to those <1.5μm particles did not get sick and viral RNA was detectable only in particles >4μm. Furthermore, viral RNA is not synonymous with infectious virus, evidenced by ferrets being most infectious at 1dpi (day post inoculation) with successively decreasing infectivity at 3dpi and 5dpi, while viral RNA from air samples followed a different course and was much higher at 5dpi than 1dpi. For a broader survey of related literature, read section 4 "Discussion" in

[Chen 2020].

These studies demonstrate that we still have a lot to learn about the importance of particle sizes for transmission, but generally suggest particles between 1 and 10μm in diameter are of concern for disease transmission.

Droplets of most concern may range from 1μm to 5μm. For example,

[Milton 2013]

collected exhaled particles from flu patients and found 8.8 fold more viral copies in the ≤5μm particles than in the >5μm particles. What's more, surgical masks were much more effective at blocking the virus from >5μμm droplets (a 25-fold decrease in viral copy numbers with masking) than from ≤5μm droplets (a 2.8-fold decrease). That's a double whammy for the smaller particles: patients emit more flu virus in the <5μm particles, and those particles are less well filtered by surgical masks. Similarly,

[Lindsley 2010]

assessed droplets expelled by coughing and found that 35% of the influenza RNA was contained in particles >4μm in aerodynamic diameter, 23% was in particles 1 to 4μm and 42% in particles <1μm. Lindsley did not assess infectivity directly. In well-controlled studies in ferrets,

[Zhou 2018]

found that droplets less than 1 μm did not cause ferret-to-ferret transmission, whereas those from 1.5 to 15.3 μm did transmit infection; larger droplets were not assessed. Zhou's results also counter the idea that high particle counts necessarily imply high infectivity: while 76.8% of total airborne particles released from the ferrets had aerodynamic diameters of 0.52-1.54μm, ferrets exposed to to those <1.5μm particles did not get sick and viral RNA was detectable only in particles >4μm. Furthermore, viral RNA is not synonymous with infectious virus, evidenced by ferrets being most infectious at 1dpi (day post inoculation) with successively decreasing infectivity at 3dpi and 5dpi, while viral RNA from air samples followed a different course and was much higher at 5dpi than 1dpi. For a broader survey of related literature, read section 4 "Discussion" in

[Chen 2020].

These studies demonstrate that we still have a lot to learn about the importance of particle sizes for transmission, but generally suggest particles between 1 and 10μm in diameter are of concern for disease transmission.

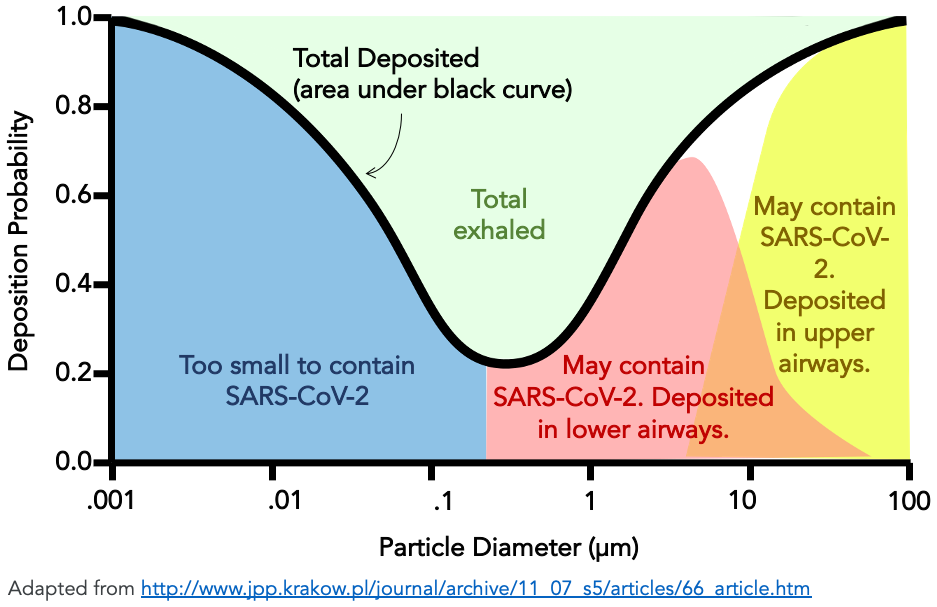

Particle Deposition.

Where in your body a particle lands matters, too, and it's well established that particles of different sizes tend to deposit in different places

[Hinds 1999].

According to

[Carvalho 2011]

particles between 1 and 5 μm are deposited deep in the lungs, whilst those larger than 10 μm are generally deposited in the oropharyngeal region, and most particles between 0.1 and 1 μm are exhaled (See figure). In fact, an estimated 75% of particles between 0.2 and 0.8 μm are exhaled and therefore are not deposited in the lungs

[Sosnowski, 2021].

Although ultrafine particles (i.e., nanoparticles) can be deposited in the lungs and may be important in industrial settings, these particles are too small to contain the SARS-COV-2 virus and are not likely to be relevant in the transmission of COVID-19

[Sosnowski, 2021].

Where in your body a particle lands matters, too, and it's well established that particles of different sizes tend to deposit in different places

[Hinds 1999].

According to

[Carvalho 2011]

particles between 1 and 5 μm are deposited deep in the lungs, whilst those larger than 10 μm are generally deposited in the oropharyngeal region, and most particles between 0.1 and 1 μm are exhaled (See figure). In fact, an estimated 75% of particles between 0.2 and 0.8 μm are exhaled and therefore are not deposited in the lungs

[Sosnowski, 2021].

Although ultrafine particles (i.e., nanoparticles) can be deposited in the lungs and may be important in industrial settings, these particles are too small to contain the SARS-COV-2 virus and are not likely to be relevant in the transmission of COVID-19

[Sosnowski, 2021].

Evidence from animal studies (SARS-COV-2): A hamster study with SARS-CoV-2 [Port 2020] showed that method of inoculation affects the course of disease. Hamsters were exposed to SARS-CoV-2 through: fomites from living in a cage previously occupied by an ill hamster, intra-nasal inoculation with a swab, aerosol consisting of 1-5μm particles from a nebulizer, and aerosol from an ill hamster in an adjacent cage. Airborne transmission was more efficient than fomite transmission, and the aerosol-exposed hamsters had more virus in their lungs and more severe outcomes in all regards. While this was a small study and the dosages were not calibrated to match expected real-world exposure levels, it’s clear that type of exposure affects disease course.

What can we conclude from all that? Particles 1μm to 10μm are both copiously produced and readily deposited in the body, so this size range is likely of key concern. Particles >10μm are likely of moderate concern, since a large droplet has large volume but apparently lower viral density than smaller droplets, and these larger droplets are generally filtered well by most fabrics. Particles less than 1μm may be of lesser concern since most are exhaled and not deposited in the body. Droplets between 1 and 5μm may be the greatest challenge to mask-makers since these particles are large enough to contain the virus and are not easily blocked by masks.

This content will soon be featured as a guest blog post at MakerMask.org

Originally written in Google Docs: Filtration and particle sizes (draft)

Last updated 30 May 2021 © Anna MitrosBack to Ania's Home Page